The big picture: Firmware is one of those obscure areas of computing that is simultaneously critical yet largely ignored. Not coincidentally, we have been doing a lot of work lately digging around such dark corners of the industry. Despite the ubiquitous nature of firmware, almost no one talks about it much.

Private equity firm THL announced plans to acquire AMI last week for about $600 million. AMI is a leader in firmware for compute devices, especially in the data center. When we first heard about this deal, we had to double-check which AMI this was. There have been a few companies with similar names over the years, and who even thinks about firmware anymore? Not many people, apparently.

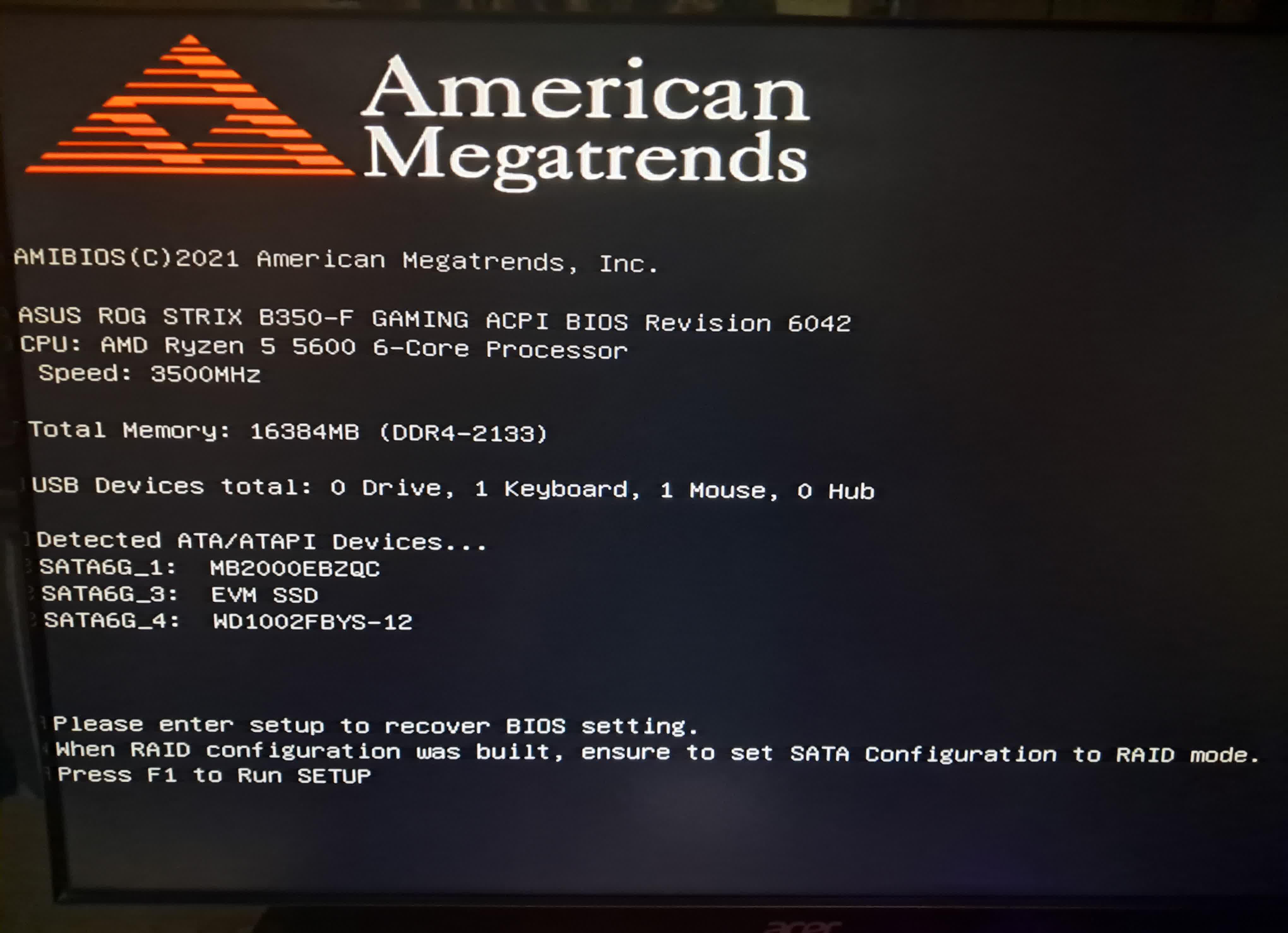

Firmware is software that sits between a processor and the operating system of a computer. It includes categories like BIOS/UEFI – connecting the processor to all the other elements of the system – and various embedded security features. AMI provides firmware for PCs, smartphones, and, most importantly, servers.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

As we have discussed a few times recently, servers come in a whole range of variations. Every server design ends up being a little different – mixing and matching CPUs, GPUs, ASICs, memory, networking, storage, and power components to an infinite degree.

When the CPU powers up, it needs to know what hardware components it has to work with, and the firmware makes all this happen.

This is messy work. Firmware engineers need to understand all the low-level primitives of this hardware. Typically, they work with processor designers years ahead of chip launches. This way, when chips start coming back from the fab, they can be configured into servers quickly.

This is not the fancy design work that chip companies like to do, nor is it the cutting-edge software that hyperscalers focus on. It is critical, but no one gets very excited about it.

Enter AMI. AMI got its start designing firmware for PCs. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, this was a huge business because PCs were so new, and the Windows ecosystem was evolving rapidly. They made the transition to smartphones in the 2000s. And as cloud servers blossomed, they added that capability as well.

Their presence in smartphones has been less prominent compared to their dominance in servers, however they are essentially the only company that was able to stick all three of those landings. Many of their competitors fell away over the years, never successfully moving into new product lines.

While some ODMs and OEMs can design basic firmware, their solutions are often not robust enough for large-scale production. Today, almost any company that wants to design a server but does not want to write its own firmware needs to work with AMI.

Also read: How to build a server in "100 easy steps": The growing pains of modern data centers

And, of course, this is happening just as data centers are becoming ever more heterogeneous and complex. Some hyperscalers, like AWS and Google, are designing their own CPUs and AI ASICs. Data centers are transitioning from CPU to GPU to accelerators.

All this means that the work of building firmware is becoming harder and more important. We have written about the difficulties in standing up large-scale GPU clusters, and part of that challenge stems from the need for companies to deliver better firmware.

Dig a bit into server designs, and the difficulties start to emerge – thus the opportunity for AMI.