Why it matters: In the new digital age, CDs and DVDs have become relics, replaced by the popularity of streaming and cloud storage. However, scientists think they may have found a way to bring optical disc storage roaring back – with a massive upgrade that massively increases data density.

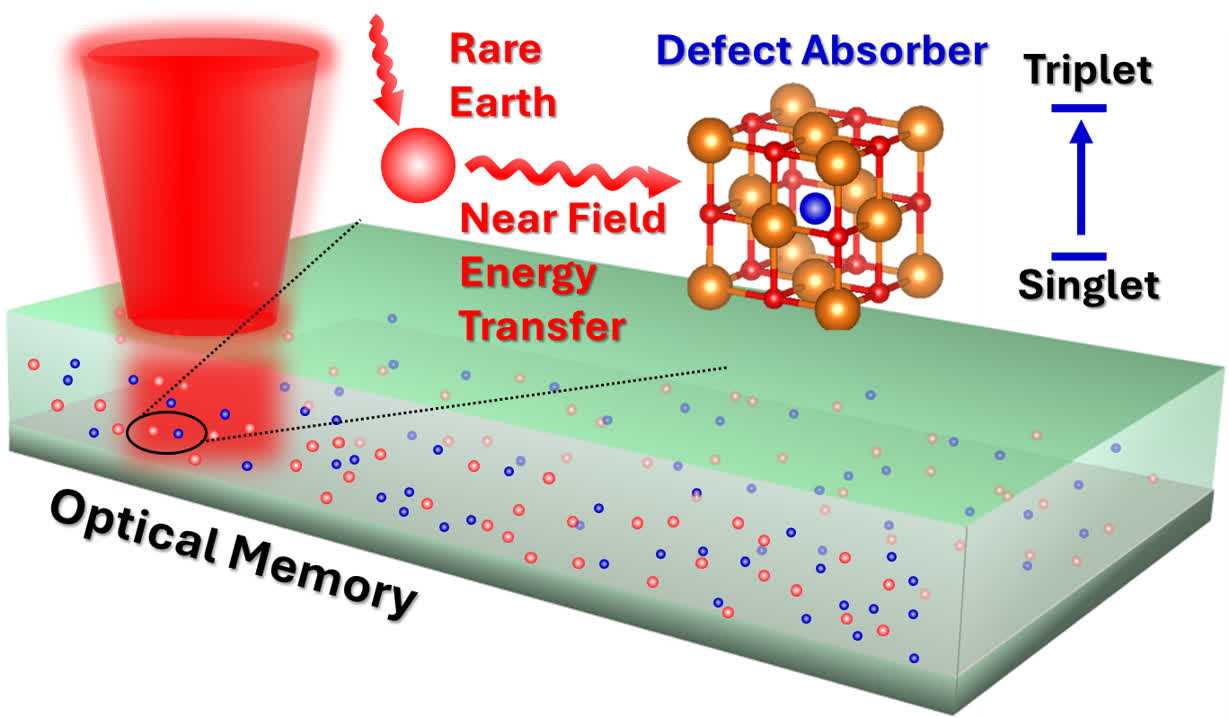

Researchers at the University of Chicago and Argonne National Lab have developed a new type of optical memory that stores data by transferring light from rare-earth element atoms embedded in a solid material to nearby quantum defects. They published their study in Physical Review Research.

The problem that the researchers aim to solve is the diffraction limit of light in standard CDs and DVDs. Current optical storage has a hard cap on data density because each single bit can't be smaller than the wavelength of the reading/writing laser.

The researchers propose bypassing this limit by stuffing the material with rare-earth emitters, such as magnesium oxide (MgO) crystals. The trick, called wavelength multiplexing, involves having each emitter use a slightly different wavelength of light. They theorized that this would allow cramming far more data into the same storage footprint.

The researchers first had to tackle the physics and model all the requirements to build a proof of concept. They simulated a theoretical solid material filled with rare-earth atoms that absorb and re-emit light. The models then showed how the nearby quantum defects could capture and store the returned light.

Also see: Anatomy of an Optical Drive - How the Tech Works

One of the fundamental discoveries was that when a defect absorbs the narrow wavelength energy from those nearby atoms, it doesn't just get excited – its spin state flips. Once it flips, it is nearly impossible to revert, meaning those defects could legitimately store data for a long time.

While it's a promising first step, some crucial questions still need answers. For example, verifying how long those excited states persist is essential. Details were also light on capacity estimates – the scientists touted "ultra-high-density" but didn't provide any projections against current disc capacities. Yet, despite the remaining hurdles, the researchers are hyped, calling it a "huge first step."

Of course, turning all this into an actual commercial storage product will likely take years of additional research and development.