Why it matters: For decades, Miranda – the small, icy moon of Uranus – was thought to be nothing more than a frozen hunk of rock and ice. However, new research from Johns Hopkins University is challenging that assumption in a big way. The findings suggest that Miranda may actually harbor a subsurface ocean, potentially even capable of sustaining life.

"To find evidence of an ocean inside a small object like Miranda is incredibly surprising," said Tom Nordheim, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab who worked on the study.

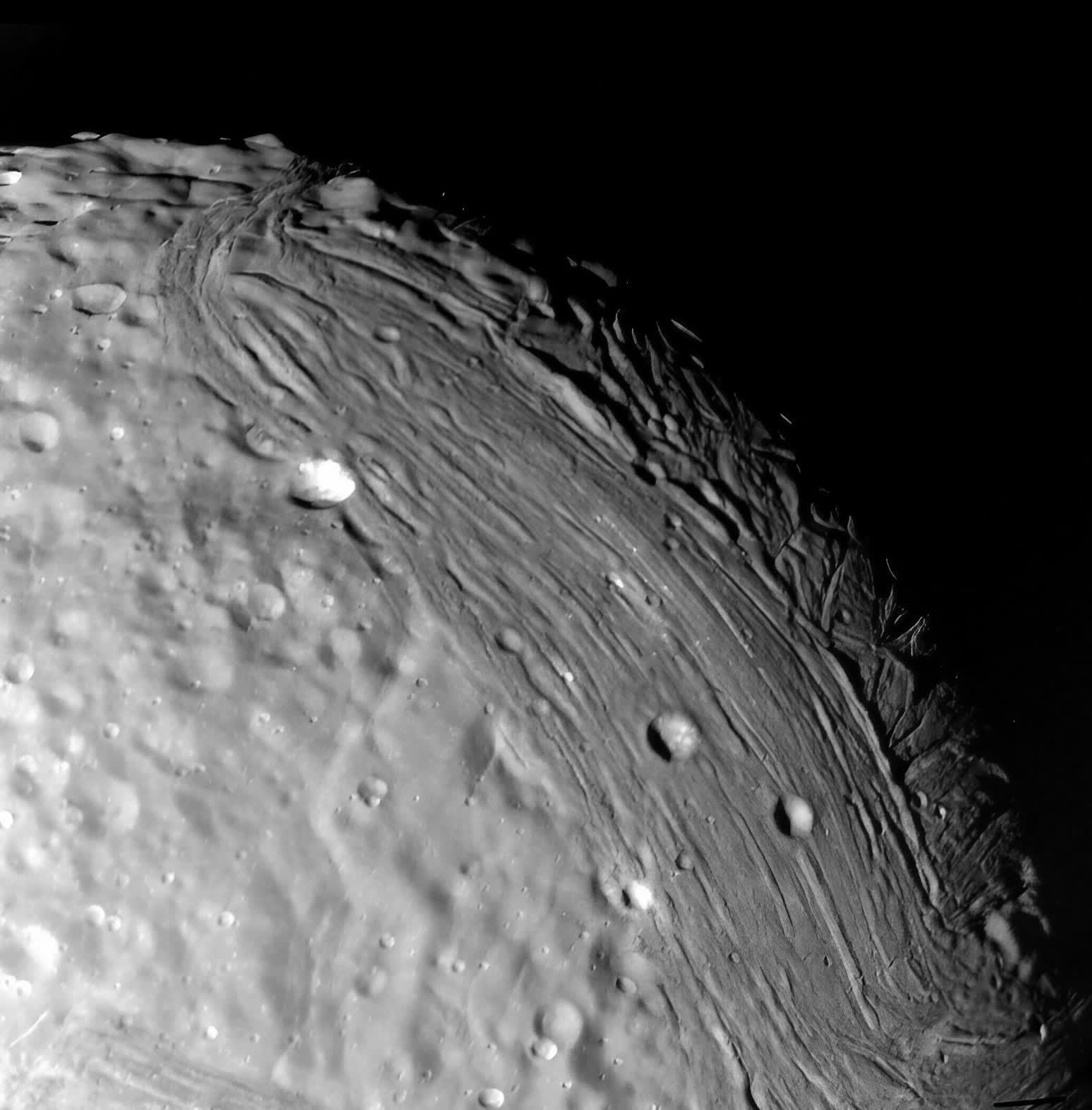

Miranda is the smallest of Uranus's major moons, measuring just 290 miles across – about one-seventh the size of Earth's moon. Since the Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by in 1986, capturing several photographs, the prevailing belief has been that Miranda, like Uranus's other natural satellites, is primarily composed of ice mixed with rock.

Recently, however, scientists revisited those decades-old images and data, applying modern modeling techniques and a fresh perspective. By mapping Miranda's rugged, heavily cratered surface and comparing pattern alignments, they built a compelling case for the moon concealing a liquid ocean layer beneath its icy shell.

Their models suggest that Miranda likely harbored a subsurface ocean about 62 miles deep beneath a frozen layer roughly 19 miles thick, between 100 and 500 million years ago. Even more surprising is that this ocean may have been warm enough to remain liquid, despite Miranda's extreme distance from the Sun.

If true, the source of Miranda's internal heating could be attributed to a gravitational "dance" with Uranus's other moons, a process known as orbital resonance, which generates enough frictional heat to prevent complete freezing over long timescales. Researchers speculate there's a real possibility that some liquid could remain beneath Miranda's surface even today.

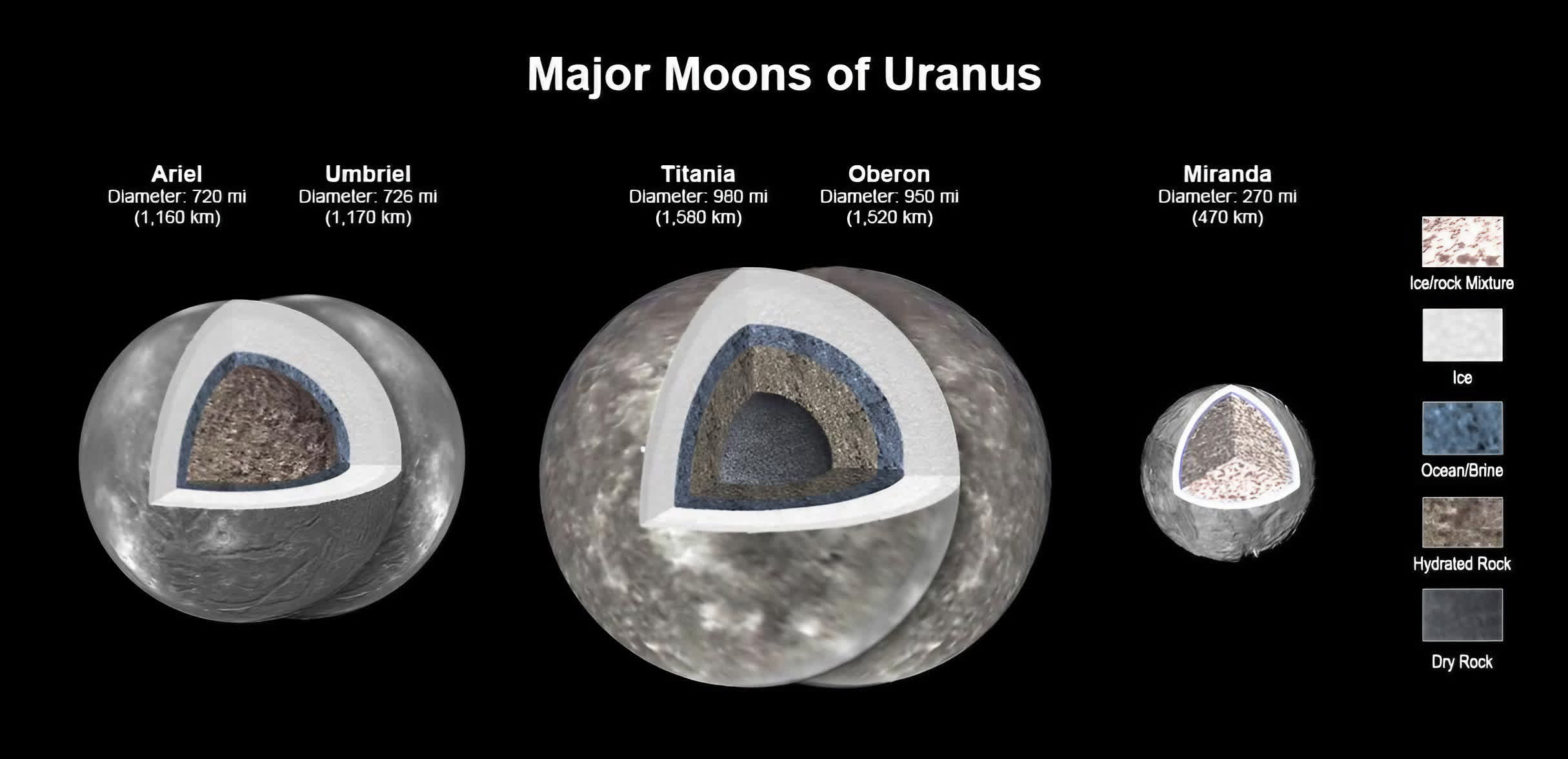

Miranda wouldn't be alone in the "ocean moon" category, either. NASA's recently launched Europa Clipper is en route to investigate a suspected subsurface ocean on Jupiter's moon Europa. This ambitious mission will travel 1.8 billion miles over six years to reach its target. Last year, NASA also examined Uranus's moons Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon for similar evidence of subsurface water layers.

Other candidates include Saturn's moons, Enceladus and Titan. As we explore further, it seems that subsurface oceans may be relatively common on icy moons throughout the solar system.

While NASA hasn't scheduled a mission to Miranda just yet, these findings may help spark interest in sending a robotic explorer back to study the moon more closely.

As Nordheim put it, "We won't know for sure that it even has an ocean until we go back and collect more data. We're squeezing the last bit of science we can from Voyager 2's images. For now, we're excited by the possibilities and eager to return to study Uranus and its potential ocean moons in depth."