What just happened? Researchers in Sweden have developed a new type of conductive silk thread that can transform textiles into thermoelectric generators. The innovative material harnesses the temperature difference between the wearer's body and the surrounding air to generate an electrical current.

The team from Chalmers University of Technology coated ordinary silk threads with a specialized polymer that is both flexible and stably conductive, addressing a major challenge in developing wearable power sources. By using materials that reliably convert heat into electricity while remaining soft, safe, and comfortable, they've made a breakthrough for wearable tech.

"The polymers that we use are bendable, lightweight, and easy to use in both liquid and solid form. They are also non-toxic," explained Mariavittoria Craighero, a doctoral researcher at Chalmers and the first author of the study. The full research can be found in the Advanced Science journal.

In earlier work, the team relied on metallic threads to maintain conductivity in air, but the new thread uses a recently developed polymer that is not only highly conductive but also exceptionally stable when exposed to air. This innovation allows the researchers to eliminate the need for rare earth metals.

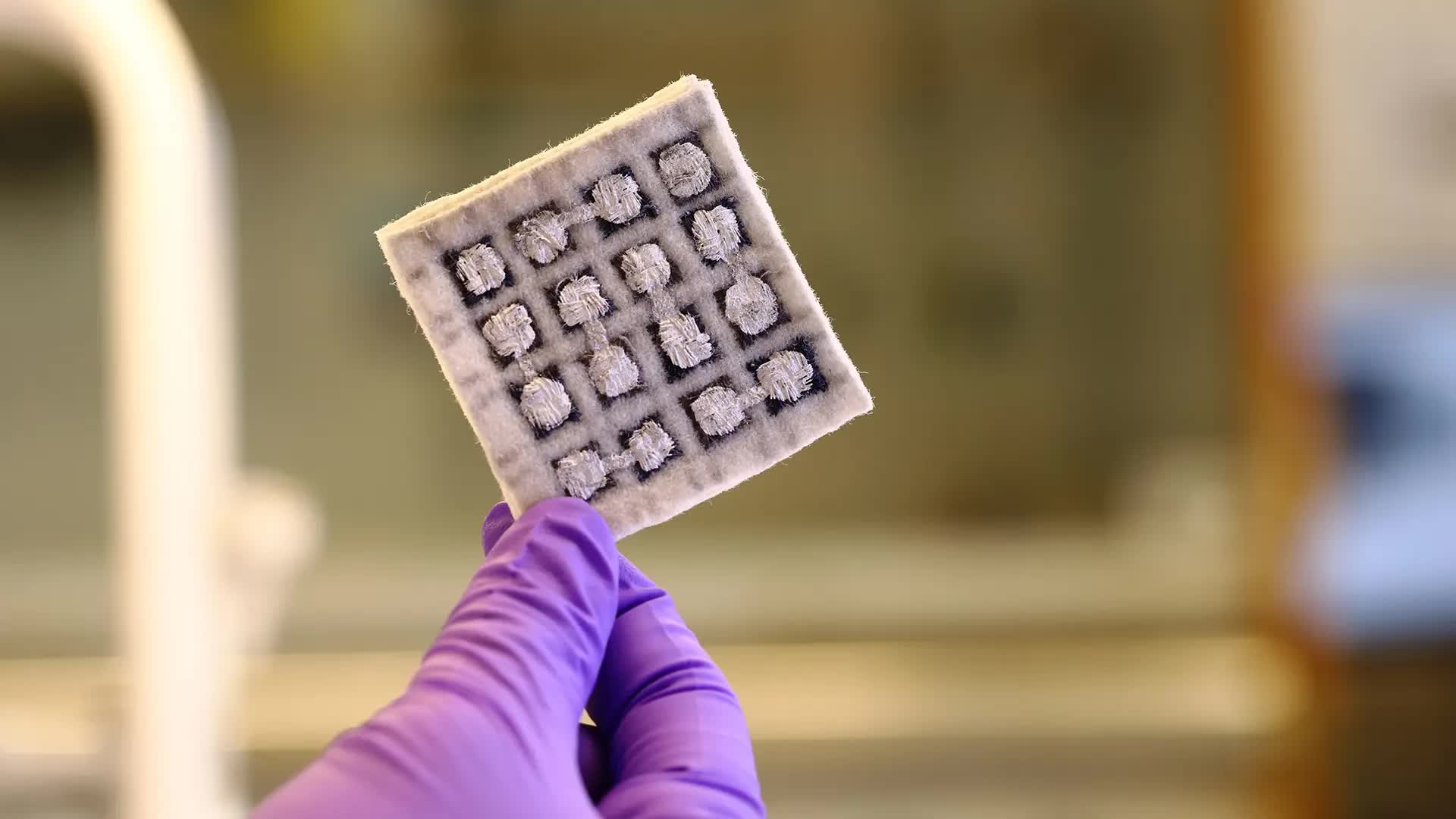

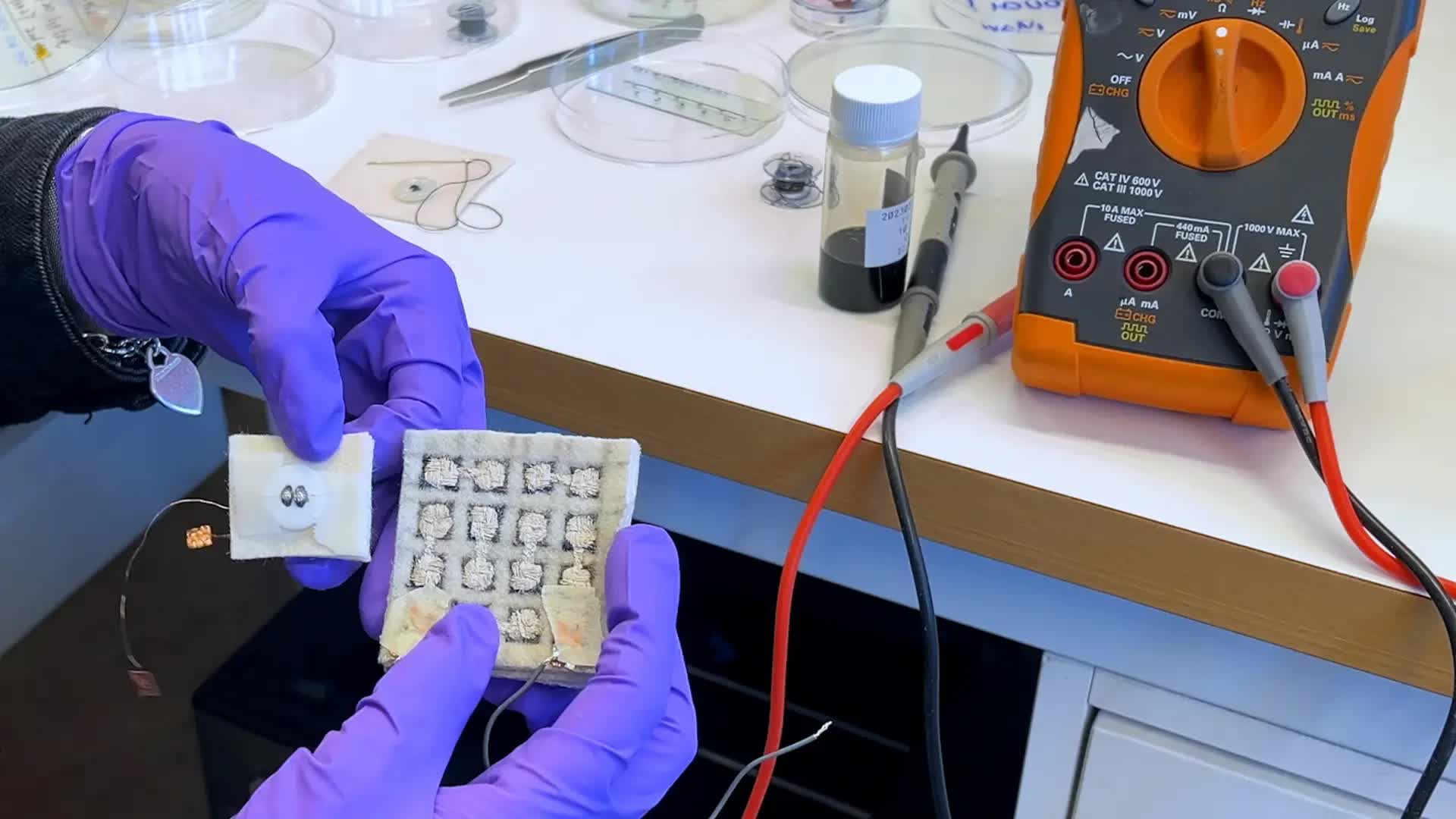

To demonstrate the technology, the researchers integrated the conductive threads into a fabric swatch and a button. When placed between hot and cold surfaces to create a temperature differential, the thermoelectric textiles generated a voltage proportional to the temperature difference, producing around six millivolts from a 30 degree Celsius differential.

Notably, the threads retained about two-thirds of their conductivity after seven machine washes, though Craighero notes this needs significant improvement before it becomes "commercially viable." The threads have also shown stable performance in lab tests for over a year.

Of course, significant challenges remain before we can reliably power devices with high-tech threads. Currently, the sewing process is highly labor-intensive, with a single fabric sample requiring four days of meticulous hand stitching. Craighero notes that developing automated manufacturing processes will be essential for making wearable power generation commercially viable.

Furthermore, six millivolts is still modest, limiting current applications to low-power devices like thermocouples and piezoelectric sensors. Even with voltage boosts, a considerable temperature differential would be needed to generate meaningful current. The demonstrated 30 degree Celsius gap, for example, is quite wide, though the scientists remain optimistic.

"We have now shown that it is possible to produce conductive organic materials that can meet the functions and properties that these textiles require. This is an important step forward. There are fantastic opportunities in thermoelectric textiles and this research can be of great benefit to society," says Christian Müller, professor at the department of chemistry and chemical engineering at Chalmers University of Technology and research leader of the study.